Scoliosis Symptoms Types & Treatments

Scoliosis: Symptoms, Types & Treatments

Scoliosis is a sideways curvature of the spine. It tends to develop most often in adolescence, but it can also be present at birth or develop well into adulthood.

Scoliosis tends to run in families, and girls are more likely than boys to suffer from it. Severe cases of scoliosis can lead to health complications if left untreated, which is why early diagnosis and intervention (where necessary) are so important.

Ahead, you’ll find helpful information and resources about scoliosis, including what it is and how it’s treated by spine specialists today. Before we move on to specific information about scoliosis, it’s important to understand the normal anatomy of the spine.

The Human Spine

Our spine has several natural curves:

- The cervical spine (neck) curves slightly outward, away from the body

- The thoracic (upper and middle) spine curves slightly inward, into the body

- The lumbar (lower) spine curves slightly outward, away from the body

Below these regions are the sacrum (hip) and the coccyx (tail bone).

The curvature of our spine helps us bear weight, absorbs stresses, and provides us with a certain degree of flexibility. In a healthy person, the spine appears straight when viewed from behind. In those with scoliosis, the spine bends in a C-shaped or S-shaped (or backwards C- or S-shaped) curve. Except in mild cases, this curvature is often noticeable with the naked eye. Abnormal curvatures generally affect the thoracic and (less commonly) lumbar spine.

Common Signs and Symptoms of Scoliosis

Early stages of scoliosis rarely have signs or symptoms, and the severity of scoliosis can vary dramatically from person to person.

Some people have a mild spinal curvature, while others have a much larger degree of curvature.

A sideways curvature of at least 10 degrees is considered scoliosis. A 10- to 20-degree curve may not be noticeable when the person is clothed. A curvature that progresses to 20 degrees or more may be detectable—observers may notice clothing hanging unevenly or the person’s body tilting to one side.

Common signs and symptoms of scoliosis include:

- Uneven shoulder blades; one shoulder blade may stick out further than the other.

- Uneven rib cage, waist, or hips.

- Asymmetrical-looking spine.

- Leaning to one side.

- Head off-center from pelvis.

- Altered gait from hip misalignment.

- Difficulty breathing (more common in cases of severe congenital or neuromuscular scoliosis).

- Muscle spasms (more severe cases) or spine pain from trunk imbalances.

- Reduced range of motion (the spinal twisting scoliosis causes can increase the rigidity of the spine and reduce flexibility).

- Lower self-esteem, an often overlooked symptom; it can be a significant factor for those with a noticeable spinal deformity, especially adolescents; wearing a noticeable back brace, especially at school, can cause significant embarrassment and discomfort.

Types of Idiopathic Scoliosis

Most cases of scoliosis have no known cause—this is called idiopathic scoliosis. Idiopathic scoliosis is categorized into 3 types, as follows:

- Infantile idiopathic scoliosis; birth to 3 years old

- Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis; 4 to 9 years old

- Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis; 10 to 18 years old

Most cases of idiopathic scoliosis develop in adolescence, during which rapid skeletal growth typically occurs. This is why early detection and monitoring are crucial.

Additional types of scoliosis include neuromuscular scoliosis, caused by a neuromuscular disorder such as Marfan syndrome or muscular dystrophy, and degenerative scoliosis, which is associated with older adults (usually over age 40); this is caused by degeneration of the spine with aging; osteoporosis is often a contributing factor.

Common Types of Curves

The following curvatures of the spine can occur with scoliosis:

- Thoracic curve: Curve of the middle spine to the right (dextroscoliosis) or to the left (levoscoliosis); curvatures to the right are more common.

- Thoracolumbar curve: Curvature pattern that includes the vertebrae of the lower thoracic (middle back) and upper lumbar (lower back) regions.

- Lumbar curve: Curvature of the lower spine to the right (dextroscoliosis) or to the left (levoscoliosis).

- Double major curve: A double curvature pattern that usually involves a right thoracic curve on top and left lumbar curve on bottom. The curvature is often less obvious with this pattern, as the curves balance each other out at the top and bottom of the spine.

Diagnosing Scoliosis

It’s common for cases of idiopathic scoliosis to be first identified by a parent or teacher, at school during a routine screening, or during a checkup at the pediatrician’s office.

The Adam’s forward bend test is usually one of the first tests performed to identify scoliosis and is often included as part of routine scoliosis screening in schools.

During the test, the patient bends forward 90 degrees at the waist, with arms hanging down toward the floor. Signs of asymmetry in the spine and/or trunk, such as one shoulder blade higher than the other, rib cage higher on one side, uneven waist, body tilting to one side, and one leg appearing shorter than the other, are usually clearly visible when the person is in this position.

The person administering the test may also use a scoliometer—a device placed on the back in the area(s) where the asymmetry looks greatest; the scoliometer estimates the angle of trunk rotation (ATR).

While the Adam’s forward bend test is generally useful for identifying scoliosis of the upper or mid back, it is not as effective at detecting curves of the lower spine.

A spine doctor will take a detailed medical history of the patient, including information about growth spurts and when they occurred, birth defects, and any injuries or trauma. He or she will also perform a physical exam to test the patient’s reflexes and check for abnormal physical symptoms, including curvature of the spine. The doctor will also order one or more of the following diagnostic tests:

- X-ray: An essential diagnostic tool for scoliosis, x-rays help doctors identify the type of curves and their angle; curves greater than 20 degrees may require treatment.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This test reveals more than an x-ray alone; it uses magnetic fields and radiofrequency waves to create a detailed image of the spine; these may be used if a doctor suspects an underlying cause (non-idiopathic) of scoliosis.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan: This test uses x-rays to produce a three-dimensional image of the spine.

- Bone scan: This test uses radioactive material (injected in the vertebrae) to make details of the spine more visible.

To make a firm diagnosis of idiopathic scoliosis (the most common type), a spine specialist must rule out other types of scoliosis, including:

- Congenital scoliosis, a condition that is present from birth and is the result of malformation of the spine.

- Neuromuscular scoliosis, which can result from a number of neuromuscular conditions, including cerebral palsy and Marfan syndrome.

- Degenerative scoliosis, also called adult-onset scoliosis, caused by the deterioration of the facet joints of the spine.

- Nonstructural scoliosis, also known as functional scoliosis; it involves a temporary change of spinal curvature (e.g., from different leg length, which can be corrected with a shoe insert); nonstructural scoliosis does not present the spinal rotation seen with other types.

The spine specialist will look for three key components: sideways curvature of the spine, spinal rotation, and skeletal maturity, to make a diagnosis. This and other information, including the patient’s history and diagnostic test results, help the medical team evaluate the likelihood for progression and create a treatment plan tailored to the patient’s specific needs.

Scoliosis Treatment Options

Which treatment option is appropriate will depend on the severity and cause of the disorder. Treatment options may include:

Observation: A curve that has not yet reached 20-25 degrees may call for a “watchful waiting” approach to see if the disorder progresses on its own. Non-invasive treatments, including physical therapy or complementary alternative medicine (CAM), such as chiropractic care, may be used; CAM treatments have not been proven to halt curve progression but may help with pain.

Bracing: A brace can help halt the progression of the curvature in adolescents; bracing is appropriate for patients with a curve of more than 25-30 degrees, who are still growing, and for girls who have not begun menstruating. Read more about bracing for idiopathic scoliosis here and about the different brace types here.

Surgery: In severe cases, when the scoliosis is worsening and debilitating, surgery may be necessary. Surgery is recommended for curves of greater than 45 degrees that are progressing. Scoliosis surgery can help correct the curve and stop it from getting worse (in patients who are still growing), and surgery may also be recommended by a spine surgeon for patients who are experiencing heart or lung problems due to scoliosis. Read more about surgery for scoliosis here.

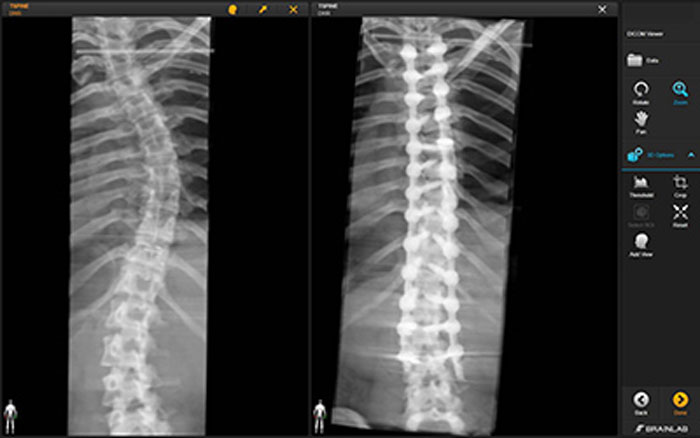

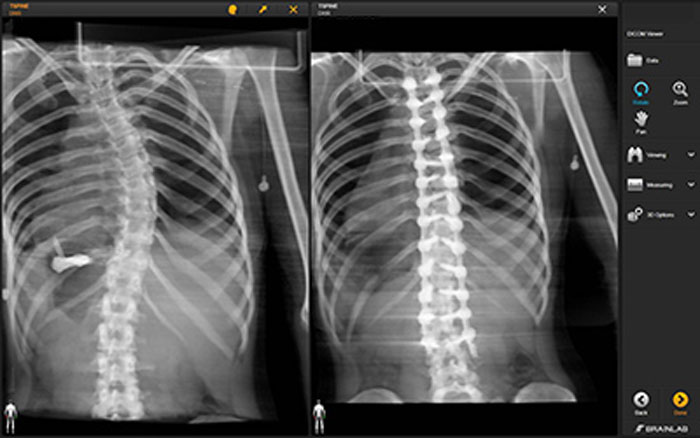

The before and after pictures below show the dramatic difference spine surgery can make for patients with scoliosis.

Scoliosis Care at Och Spine at NewYork-Presbyterian at the Weill Cornell Medicine Center for Comprehensive Spine Care

If you suspect your child may have scoliosis, don’t wait — see a spine specialist right away. Time is of the essence when it comes to diagnosing and treating this condition.

The expert spine doctors at our spine care center are committed to providing the highest level of patient-centered care for scoliosis and the entire spectrum of back and neck conditions.

Kai-Ming Fu, MD, Ph.D., is a board-certified neurosurgeon at the Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery. Dr. Fu combines his clinical interests in deformity, reconstructive, revision, and tumor surgery with active research in clinical outcomes. His work has been presented at multiple national and international meetings and been published in journals such as Spine, Journal of Neurosurgery, Neurosurgery, Journal of Neurophysiology, and Journal of Neuroscience.

He has been nominated for and won multiple awards at meetings such as the Scoliosis Research Society Annual Meeting and the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. His work has been featured in Spinal News and Orthopedics Today. Call 212-746-2260 to schedule an appointment with Dr. Fu.

About Och Spine at NewYork-Presbyterian at the Weill Cornell Medicine Center for Comprehensive Spine Care

Our spinal care center is a state-of-the-art clinical facility staffed by an expert team of physicians, nurses, and therapists dedicated to helping patients with back pain and all types of spine-related conditions and injuries.

The spine care team works collaboratively with Weill Cornell Medicine’s Imaging at NewYork-Presbyterian to provide patients with the most accurate diagnosis possible, as well as the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine to provide patients with regenerative medicine treatment options. Please call 888-922-2257 to schedule an appointment with one of our providers, or use our contact form for general inquiries.

We’ve Got Your Back

For more information about our treatment options, contact our office today.