Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus an Eccentric Exercise Program for Chronic Tennis Elbow

Point/Counterpoint

Guest Discussants: Joseph Ihm, MD, Kenneth Mautner, MD, Joseph Blazuk, MD

Feature Editor: Jaspal Ricky Singh, MD

What is tennis elbow?

You don’t have to play tennis to suffer from lateral elbow tendinopathy (also called lateral epicondylitis and tennis elbow), a condition that affects 1 to 3% of the population.

Typical symptoms include pain and tenderness on the outside of the elbow. Pain can also spread along the forearm to the wrist. Inflammation was first believed to cause tennis elbow, but physicians now understand that it is caused by repetitive overuse of the forearm. Heavy manual labor increases the risk for this condition.

To better understand tennis elbow and its treatment, it is important to understand the elbow’s anatomy. The elbow joint is made up of the upper arm bone (humerus) and the two bones in your forearm. There are bony bumps at the bottom of the humerus called epicondyles; the bump on the outside of the elbow is called the lateral epicondyle.

Muscles, ligaments, and tendons hold the elbow joint together. Repetitive overuse of the forearm negatively affects how the hand and wrist muscles work together, causing discomfort and pain. With chronic tennis elbow, the extensor tendon often breaks down.

How is tennis elbow diagnosed?

To diagnose tennis elbow, a physician performs a physical exam during which he or she applies pressure to the affected area or asks the patient to move the elbow, wrist, and fingers in various ways. In many cases, the patient’s medical history and physical exam provide enough information for a diagnosis. In some cases, an ultrasound or another type of imaging test may be needed to diagnose tennis elbow or to rule out other causes of the symptoms.

How is it treated?

Tennis elbow often improves on its own with rest and over-the-counter pain medications. If pain persists, the following treatment options may be recommended.

- Therapeutic ultrasound: A special needle is inserted into the damaged portion of the tendon. Ultrasonic energy vibrates the needle, liquefying the damaged tissue to be suctioned out.

- Friction massage: A deep-pressure massage is performed at the site of the injury to break down scar tissue and return it more flexible, pliable, and more functional tissue.

- Counterforce elbow band or strap: A compressions strap goes around the forearm just below the elbow to reduce tension on the tendons at the elbow by transferring force farther down the arm.

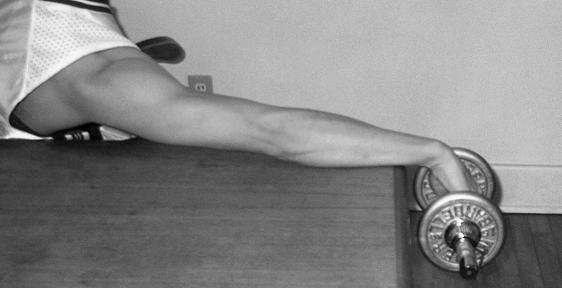

- Eccentric exercise strengthening: A form of resistance exercise that strengthens and lengthens the muscles and tendons of the forearm by applying a weight, for example, lowering the wrist very slowly after raising it.

- Percutaneous tenotomy: This procedure involves gently passing a needle through the abnormal tendon multiple times (sometimes called “needling”) to change a chronic degenerative process into an acute condition that is more likely to heal.

- Injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP): A patient’s platelets are injected at the site of the injured tendon. Injured tendons heal slowly because they get little blood and the blood platelets attract healing growth factors.

- Injection of autologous blood: An injection of the patient’s blood (sometimes done in conjunction with tenotomy)

- Surgery: The removal of damaged tissue

In the June 2015 issue of Pain Management & Rehabilitation Journal, three physicians shared differing opinions about treating tennis elbow. A patient’s case is presented here, followed by a debate as to the best treatment plan. Dr Joseph Ihm advocates for an eccentric exercise strengthening program to provide long-term relief. Drs Kenneth Mautner and Joseph Blazuk assert that an injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is warranted to optimize and restore this patient’s long-term function.

Patient case

Samuel, a 48-year-old male, has been experiencing persistent pain in his left elbow for the last 3 months. Samuel now has difficulty performing his work duties, especially gripping and lifting. He has also stopped playing recreational tennis and golf. The pain averages 5 out of 10 on a visual analog scale (VAS) and is usually a deep ache, but can be sharp at times.

Samuel’s initial treatment was physical therapy, including therapeutic ultrasound, friction massage, and use of a counterforce strap. After 8 sessions, the pain improved minimally. He was then referred to a sports medicine specialist.

Samuel’s physical examination shows that his extensor tendon is not inflamed. The lateral epicondyle is tender and gripping causes pain. Samuel also experienced pain when he extends his elbow, wrist, and middle finger. Samuel was diagnosed with chronic tennis elbow. Given his lack of improvement with physical therapy, Samuel requested a more aggressive treatment plan.

Joseph Ihm, MD, responds

Patients with tennis elbow—including Samuel—often do not follow an optimal exercise program that addresses the tendinosis (chronic tendinitis), nor do they receive an assessment of occupational issues that may be contributing to the pain. Therefore, we should first discuss the physical therapy program that he just completed.

Samuel is involved in 2 sports that could provoke lateral elbow pain if weakness or limitations in range of motion are present in his limbs, core, or hips. If Samuel’s physical therapy did not include eccentric exercises for the wrist tendons, I recommend this be the next line of treatment.

Should Samuel undergo additional physical therapy emphasizing eccentric exercises before proceeding with more aggressive treatment, or should he now be offered a more aggressive treatment—such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection?

Although a PRP injection is potentially a good option, it may not provide significant long-term relief compared with other injections (eg, percutaneous tenotomy). Furthermore, an eccentric strengthening program is often recommended after an injection regardless.

Several studies have shown the effectiveness of eccentric exercises program on pain and function related to lateral elbow tendinopathy. A recent literature review revealed that an eccentric exercise program, either in isolation or along with other therapies, resulted in decreased pain and improved function and grip strength.

However, another study suggests that some patients with tennis elbow recover within 12 months without any treatment. Physical therapy had better results than a wait-and-see approach, but differences were not significant. Therefore, if Samuel wants to avoid active treatment, there is a good chance that his pain would improve on its own after several months.

I believe that if Samuel wants to wait and live with the pain, he will likely see an improvement during the next several months. If he wants to pursue an active treatment that will likely improve his pain within the next several weeks, I recommend an eccentric exercise program for the wrist extensors that is performed 1-2 times per day: 3 sets of 15 repetitions for 6-12 weeks.

With an eccentric exercise program, there is a better chance that the tendon will improve than if no treatment is pursued. In addition to performing eccentric exercises, cross-friction massage, wrist extensor stretching, or use of a forearm brace can still be performed. Samuel’s activities and ergonomics at work should also be discussed in detail to determine if changes in his work environment could be beneficial.

Although an injection with PRP is an option, PRP may not improve pain any faster than an eccentric exercise program. Because patients receive physical therapy with a strengthening program after an injection regardless, it makes sense that Samuel should have a trial of optimal physical therapy before pursuing an injection.

With an adequate trial of a wrist extensor eccentric strengthening program, as well as an assessment and optimization of his work and sports habits, Samuel’s tennis elbow pain will likely improve without the need for an injection of any kind.

Kenneth Mautner, MD, and Joseph Blazuk, MD, respond

Tennis elbow is a problem frequently encountered in sports medicine clinics. This condition can last several months, although fortunately, it typically goes away on its own. It has been demonstrated that by taking a wait-and-see approach with no specific treatment, 83% of patients improved at 52 weeks. It is interesting to consider that we routinely prescribe physical therapy to patients who, according to this particular study, will do just as well without dedicated therapy.

Eccentric exercise certainly has proven results in treating various tendinopathies. However, some patients with chronic tendon pain, , fail to improve despite undergoing properly-performed eccentric therapy. Samuel is likely disenchanted with physical therapy, considering that its failure to resolve his pain is indeed the reason he is seeking a more aggressive approach.

A study examining tennis elbow from an occupational health perspective found that patients with high physical strain at work (such as Samuel’s job as an air conditioning repairman) and patients who experience dominant-sided symptoms are less likely to experience pain improvement without intervention.

With this in mind, we should first ensure an accurate diagnosis with an ultrasound examination. In our experience, significant findings on an ultrasound combined with risk factors, such as employment in a manual job, most often indicate a less than favorable response to conventional treatment.

If that examination shows significant changes such as thickening or tearing of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon, we would then discuss 3 treatment options:

- Wait-and-see approach

- Formal physical therapy program, including cross-frictional massage, heat, stretching, and an eccentric exercise regimen

- Percutaneous tenotomy, with or without a PRP injection

Several studies found significant improvement in patients with lateral epicondylitis after receiving 1 PRP injection. In addition, the concentration and composition of the PRP injectate was shown to influence outcomes. An injection of PRP was found to be more effective than an injection of autologous whole blood.

Finally, a multicenter, retrospective review of PRP injections for various chronic tendinopathies concluded that eccentric exercises performed after PRP injection offered no additional benefit. These considerations cast further doubt that sending Samuel back to physical therapy will yield different results.

Samuel has several known risk factors for continued pain and dysfunction despite treatment. And Samuel has already failed to respond to standard therapy. Given the lack of evidence that an eccentric exercise program will offer more benefit than the conventional physical therapy Samuel has already pursued, we believe that a non-interventional approach will not improve his pain.

Therefore, we recommend a one-time PRP procedure as a reasonable and likely cost-effective alternative to a time-intensive physical therapy protocol.

Keywords

Biomechanics: The muscular, joint, and skeletal actions of the body performed during the execution of a given task, skill and/or technique.

Eccentric exercises: Muscle contractions involve shortening and lengthening while the muscle is still producing force. The phase of contraction that occurs when the muscle shortens is concentric, whereas the phase of contraction that occurs as the muscle lengthens is eccentric. During everyday activities, concentric actions start movements while eccentric actions slow activity down. For example, when you curl a weight with your bicep and then lower it back to the starting position, the eccentric phase occurs when you are lowering the weight back to the starting position. This type of muscle contraction causes a stretch to take place within the muscle and tendon.

Tendinitis: Also called tendonitis, this condition is an inflammation or irritation of a tendon, a thick cord that attaches bone to muscle.

Tendinosis: A condition caused by a breakdown of the collagen fibers (micro-tears) within the tendon without the presence of inflammation. Unfortunately, inflammation is necessary for full healing to occur. This can lead to chronic tendinosis.

References

A complete list of references supporting this article can be found in the original journal article.